What happens in the watershed, happens in the lake!

When it comes to protecting the health of Lake Waramaug, the story does not start at the shoreline. It starts miles away in the Watershed where various forms of pollution, including stormwater runoff and erosion, begin their journey to the lake.

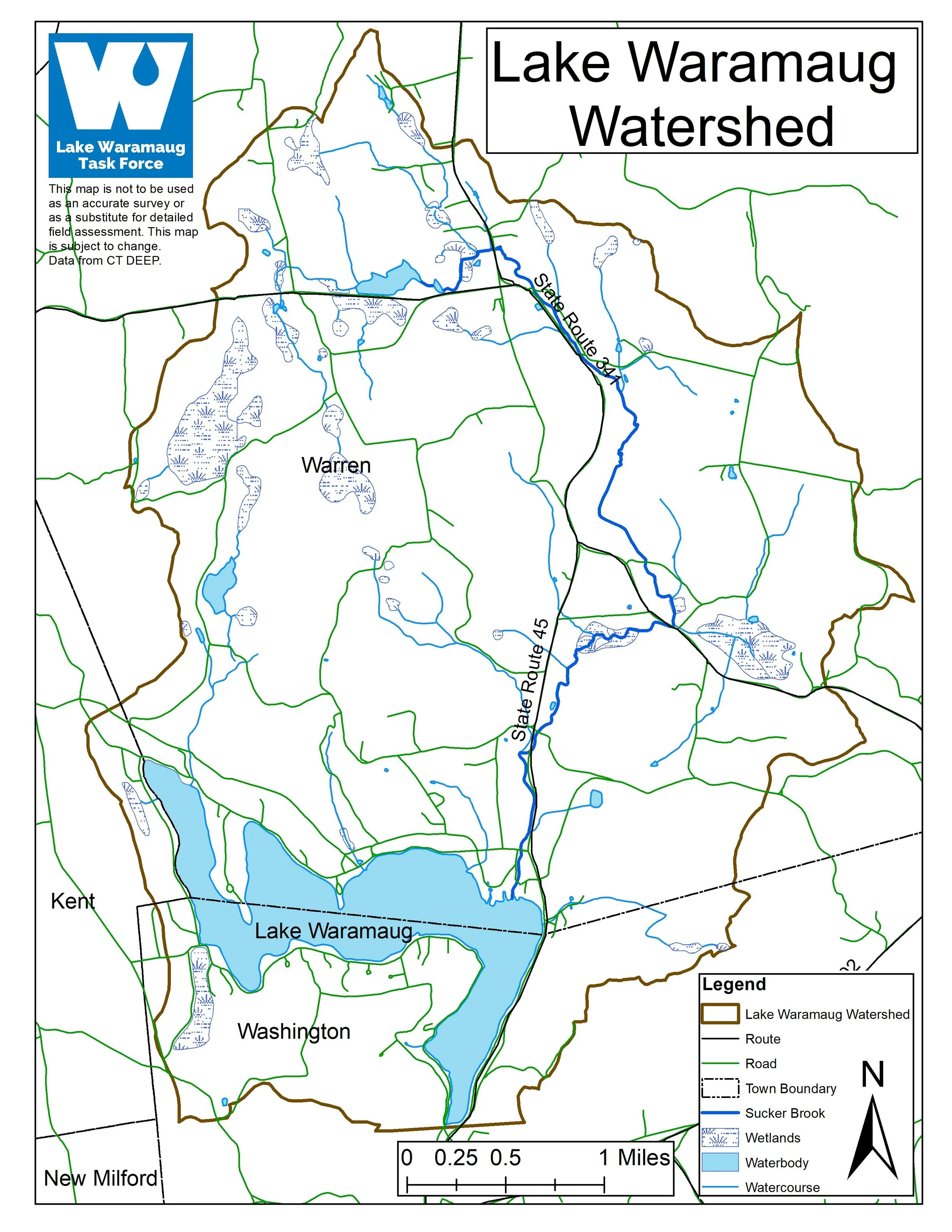

On an average day, Lake Waramaug contains about six billion gallons of water. More than half of that water comes from Sucker Brook in Warren, a town that encompasses 82% of Lake Waramaug’s 9,200-acre watershed. At our urging, the State Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) performed a comprehensive study of the water quality of Lake Waramaug and its surrounding watershed in the late 1970s. They discovered that “surface-water inflow at the northeastern corner of the lake [via Sucker Brook] was the main source of nutrients discharged into the Lake.”

Sucker Brook is still the main water source for Lake Waramaug, but other tributaries elsewhere in the Watershed also flow into the lake from Washington and Kent, as do the many storm water drains along the roads. All are potential sources of sediment and excess nutrient pollution. To keep our lake clean, clear and swimmable, we need to mitigate the risks that activity in the watershed create.

The DEEP describes watershed management as “the process of implementing land use practices and water management practices to protect and improve the quality of the water.” As climate change brings increasingly heavy rain events, wind storms and drought, we’re working on implementing greater protection strategies and protocols in Lake Waramaug’s watershed.

Nutrients and sediment from the watershed feed algae growth and diminish water clarity. Several years ago, we mapped multiple erosion sites on Sucker Brook and stabilized four of the most significant ones. Still, others need to be done to prevent further erosion. Currently, the delta at Sucker Brook (see photo above) which has been created by sediment from its banks up in the watershed, is more than two acres, a condition exacerbated by today’s severe drought conditions.

The DEEP recommends that watershed areas remain below 10% developed, and that any man-made changes use as many Low Impact Development (LID) strategies as possible. As an increase in development, such as we have seen around the Lake and in the Watershed, introduces more impervious surfaces to an otherwise natural environment carrying pollutants to the Lake, as well as making erosion problems much worse. Advocating for LID (see accompanying box) practices remains one of our major initiatives.

It costs our organization $1,000 to remove one pound of phosphorus from the lake. It‘s far more effective to keep phosphorus (and other nutrients) in the watershed growing trees, shrubs, flowers, food and fiber. Keeping nutrients in the watershed is where LID excels. And as if that is not enough to convince us all to employ the goals of LID, it is now common knowledge that projects designed and constructed to LID standards are cheaper to build out, more aesthetically pleasing, more beneficial to local ecology, more protective of wetland and water quality, and have a higher resale value as compared to projects using traditional/standard development techniques. The environmental benefits of employing the key goals of LID is why we continue to push towns to require this of every project in the watershed. It’s a rare win-win-win.

We clean out piles of watershed sediment

This August you may have seen an excavator cleaning out two sediment basins along North Shore Road in Warren. One basin is on Hawes Brook and the other is on Potash Brook. These basins, which we installed almost 20 years ago were strategically placed to capture and settle out pollution laden sediment before it reaches the lake. Sediments (eroded soils) get trapped and settle to the bottom of the basin because the basin calms turbid running water. We’ve cleaned out both basins several times since their installation, thus preventing hundreds of cubic yards of polluted sediments from degrading water quality in the lake. It is best to do so when little to no water is running in the brooks as the heavy machinery needed to remove the tons of waterlogged sediments can really stir things up. Every time we clean out these basins we take out over 200-cubic-yards of sediment. For perspective, 200-cubic-yards of material is enough to fill over 10 tri-axle dump trucks which are the largest dump trucks allowed on state highways. These basin cleanouts are important but expensive. Trying to prevent these sediments from getting into the brooks and into the basins in the first place is key to protecting the lake. That is why we all need to pay particular attention to what is happening in the watershed.